For the uninitiated, garum is the substance that was produced by the Carthaginians (and likely before by the same people in the Phoenician homelands of the Eastern Mediterranean) It was made from fish and salt and used to add a savory flavor to many foods that was otherwise lacking. it was used on everything from meat and vegetables to desserts and wine depending on how it was prepared and mixed. The Romans took over the lucrative garum production facilities from Carthage after conquest, and much of what we know about garum production comes from them.

The most recent understanding of the terminology (provided to me by Sally Grainger) is that: Liquamen refers to the whole-fish sauce made with all the viscera intact and sometimes extra viscera [presumably to speed the digestion process]. The enzymes in the viscera dissolve the fish into a thick sauce which yields a translucent, highly nutritious sauce when it is filtered or diluted. It can be gathered by skimming the top of the ferment, or by letting it drip out of the paste that has been put in a colander. It is extremely fishy, oily, and salty and packs a wallop of flavor. Allec is the solid paste that is left after the liquamen is removed. The Romans would pick this clean of bones, skin, fins and other fishy solids and use it as a paste on bread or as a condiment. Given the taste of the allec I produced, I think it would have probably been mixed with olive oil, butter or animal fat to make it more palatable. By personal choice, I would use butter. I think then it would taste like country caviar – fresh sweet butter on a hunk of brown bread spread with fresh caviar – or allec. The Romans, however, might have used olive oil.

Muria is the sauce made when the fish are gutted and headed and the liquor that emerges is weak in protein and pale in color. This probably corresponds best with the modern colatura di alici. Lastly, there is haimation which is the liquid that is produced from just from blood and viscera. This is garon haimation in Greek and garum or garum sociorum in Latin. It is black and bloody according to Galen.

Another thing that my experience making garum taught me that varied from much of the historical information available was the quantity of garum produced and the speed at which it can be harvested. Many of the early writings about garum speak of a basket being dipped into the ferment and the garum flowing into the basket. Or if a barrel or container were used, directions are to puncture the barrel near the base and let the garum flow off. This may be true for large-scale production such as those in vats, but it is not true for the casual backyard producer of garum. With 15 pounds of mackerel and almost nine pounds of salt to start, nothing flows or gushes, it is harvested drip by excruciating drip and then filtered multiple times at the same glacial rate. It takes patience and persistence – but it is worth it.

The slow speed of my garum harvest may be because of the rather high quantity of salt to fish I wound up using as well. It’s difficult to say with n=1 production experience.

After having produced garum, I am convinced that the few so-called quick recipes for “garum” in the ether cannot possibly produce the product that took nine months to create in my backyard. These recipes call for the fish and salt to be cooked on the stove top or in a yogurt maker. I’m not sure what these recipes produce – I suspect it is ordinary fish oil – but do I know that a few hours of heat cannot replace nine months of digestion. Because these authors describe the taste as, “not very fishy”, I know it cannot be garum. The garum produced by digestion is fishy, salty, and quite oily and only a few drops (vice teaspoons or tablespoons) would be needed to flavor a dish. Even if adapted from historical (usually Byzantine) sources, these quick recipes produce a product that looks like garum, but doesn’t taste like it. You can’t rush perfection.

Although the production of garum is not smelly, harvesting garum can be, unless steps are taken to minimize the smell. You must cover containers that are used to harvest and filter the garum, wear old clothes and be prepared to do lots of dishes. For the sensitive, I suggest surgical gloves – the odor permeates everything and is very hard to get rid of. Lastly if you share your home with four-legged creatures, you will want to put them out or at least keep them away from the garum – they will be curious, and noisy.

So, what does it look like? Interestingly, my garum is roughly the same color as its last living relative in the west – colatura di alici – the modern Italian fish sauce made from anchovies. The garum is a bit more amber in color (as opposed to the colatura’s reddish brown color) even after five filtrations, but the color is much more similar than that of nuoc mam which comes in a variety of shades of dark brown. The garum is also a bit more viscous than either of the two modern sauces – possibly due to the introduction of water in the modern production process, or possibly due to the different species of fish used. If you are curious about the possible west-to-east flow of fish-sauce production technology in the ancient world, please see this essay.

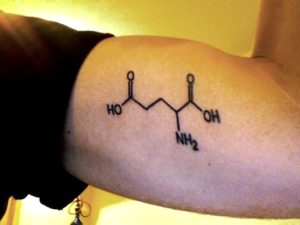

So, what does it taste like? It is saltier, way more fishy and a bit oiler than either the colatura di alici or the nuoc mam. Garum from mackerel is more powerful as it hits the tongue, has a longer crest of flavor and remains stronger for a longer period of time as it fades. One can taste it in more places in the mouth than the colatura or nuoc mam as well. No matter where you place the garum – the flavor explodes in your mouth. There is also a slight bitterness to the garum that is absent from the colatura or the nuoc mam. Interestingly, the nuoc mam has fructose and hydrolyzed vegetable protein listed as ingredients. These certainly affect the flavor of the sauce – especially the fructose. In short, the colatura and the nuoc mam taste more like each other than like the garum. The nuoc mam has a more complex flavor than the colatura, but since both are made from anchovies, that probably is because of the added ingredients listed above. The colatura claims only anchovies and salt as ingredients. Garum is, without a doubt, umami in a bottle.

Kikunae Ikeda, the Japanese chemist who “discovered” umami worked with kombu a type of seaweed that Japanese cuisine uses in many dishes either as a vegetable or dried and dissolved in broth form with bonito fish flakes as dashi. Ikeda coined the word “umami” from the Japanese “umai” which means delicious, nice or palatable as well as brothy, meaty or savory. Both sets of meanings, as you can see, represent important aspects of umami taste perception.

Getting back to production, we digested the mackerel in salt in the backyard for nine months. In the initial stages, we stirred the batch at least once a week, but as the fall and winter passed, the stirring decreased to only a couple of times a month. To harvest the garum, first skim off any that rests on the top of the vat. I did this with a teaspoon with the same technique as which I use to clarify butter or remove excess fat from the top of a stew or curry.

Next, fill a small colander with ferment pick out the large solids like bones and fins etc. Wipe the outside surface of the colander and place above a receiving vessel. Cover the colander with a plate to reduce odor and set in a place where it will not be disturbed. I suggest placing in a garage or cellar, if left out of doors, local animals will easily remove the plate and make a mess of the ferment.

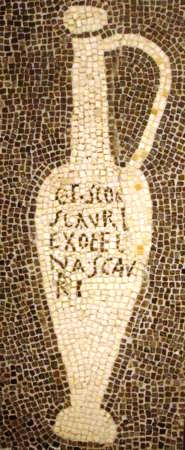

Every day a little more liquamen will drip out of the ferment. Collect this and set aside. There is no need to refrigerate – garum is so salty it will keep at room temperature nearly indefinitely. However, it may be better to harvest and filter only what you need for short-term purposes as the biochemistry of the liquamen may change over time after it is exposed to light (which is why the Romans stored it in opaque amphorae.

Next comes the filtration. The first filtration I did with commercial grade cheesecloth that was folded over into four layers. This will remove the crude solids. Then I switched to a funnel and commercial coffee filter and filtered the mixture four more times, each time after a period of rest to allow the solids to collect on the surface of the garum.

A word about garum being “clear”. On the internet, the quick recipes for “garum” all mention that the product should be “clear”. This concern is based on the concept of turbidity and is a caution against growing microorganisms instead of facilitating the enzymatic digestion of fish. With the quick production method, this may be an issue, but it is not if you go about it over a series of months. Garum isn’t clear and will never be clear with manual filtration. Even after four passes with coffee filters, if the garum is allowed to sit, a thin layer of scum forms on the top of it. If this is disturbed, the whole solution will become cloudy, only to settle out when left to rest for several hours or overnight. The best that garum will ever be is a beautifully translucent amber. Greater clarity could be achieved with a centrifuge, but that is out of reach for most people, and certainly never occurred to the Carthaginians, Greeks or Romans.

Where do we go from here? We keep on harvesting the garum. First by letting the liquid drip out of the raw ferment and then by performing dilutions with water of the allec that remains from the first harvest. Then comes the fun part. We start making the various mixtures that have been handed down to us from the Romans – using sweet and dry wine must, water, honey and olive oil and a variety of different spices. Then, well then, comes the cooking. So stay tuned. There will be much more to learn about garum in coming months. (Words by Laura Kelley; Photo of Homemade Garum by Laura Kelley; Other images from Wikimedia).

I, too, have made garum, real garum, and I couldn’t be happier with it (if I may, I made a youtube clip about it https://youtu.be/6MDHqY8prE0, which also has a link to another very short one about filtering).

I left mine for 6 months in the warm Melbourne sun, and now that we’re coming into Autumn I’m still going to leave it to age for a further 3 months – so pretty much the same as you. However, I couldn’t wait to taste it after 6 months so filtered a little, as per my video….and Oh my! Isn’t it delicious!

I am no stranger to fish sauce and have loved it for decades, I started off using Squid Brand but now find that to be more salt than flavour, so now I’ve got to the stage where I have a favourite brand (Red Boat by a mile, but Megachef for everyday cooking). But garum is different. Smoother somehow, certainly less salty (mine used 18% salt though I think one may get away with as low as 12% without producing a lethal poison!), but the fishiness is not overpowering at all – it merely adds a delicious savoury flavour. I have been poaching eggs and sprinkling a few drops over them instead of salt.

Having made one batch which will yield at least 2 litres if not more, I am going to make 2 batches next year, with mackerel and sardines separately, and see if there is much of a flavour difference.

I am also trying to find a sympathetic fishmonger who might save the guts and gills of tuna for me to attempt hymation.

Hi Tim:

Nice to meet a kindred garum producer!

You might try an Asian market to score your fish innards for a haimation run. They may look at you oddly, but they will give/sell the innards after gutting your fish for you. Good luck! keep us posted.

Laura