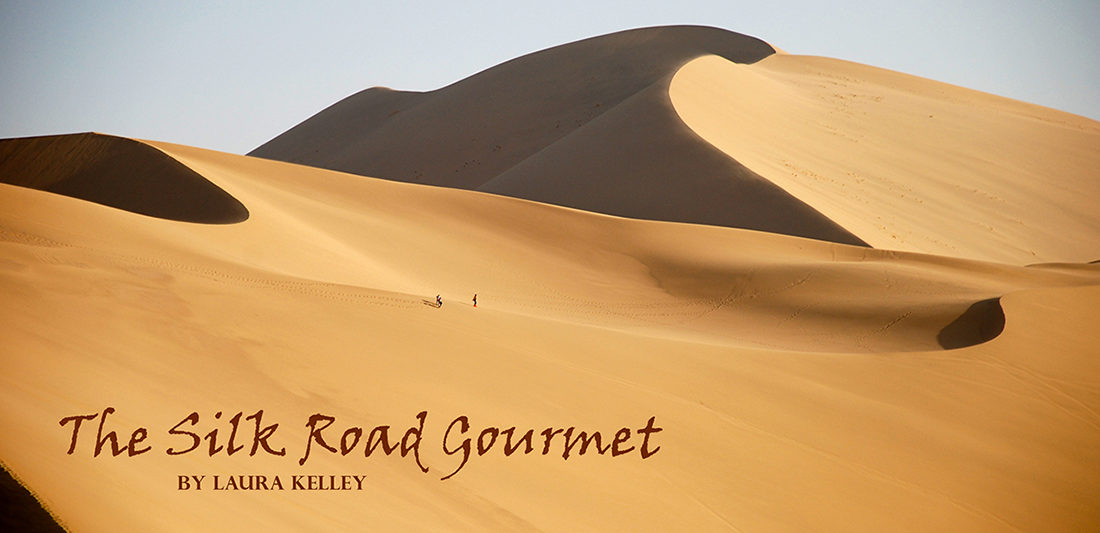

For some travelers along the Silk Road wanting to trade the unsurvivable Taklimakan desert for the inhospitable Gobi, this scene played out thousands of years ago. For me, it was last month during my visit to Turpan, China.

In April, the temperatures at nearby Flaming Mountain – the hottest place in China – topped 50 degrees centigrade. The extreme temperatures (which rise as high as 83°C) occur here because of the high iron content of the mountain and surrounding soil eroded from its great flanks, low elevation (500 feet below sea level) and in most places beyond Turpan, little to no ground cover. What is now desert was a little more fertile during the hey-day of the Silk Road, but still, the area beyond the Turpan oasis was a harsh place.

In Turpan and surrounding areas this means two things: grapes and corn. Other crops produced from irrigated lands in the region include melons, pears, and apricots, but grapes and corn are by far the most important agricultural products. Translating this to the table, Turpan is awash in a wide variety of sweet raisins and wine. As a Uyghur city, the raisins are enjoyed by everyone and the wine is for tourists and for the burgeoning Han population that is increasing in leaps and bounds as Xinjiang province develops.

Interestingly, grapeleaves and cornstalks (supplemented with salt and sugar) also form the basis for much of the animal fodder in Turfan, and yes, the taste of the grapeleaves comes through in the tender, sweet meet mutton enjoyed in the area – the best pastorally derived meat I have ever tasted. According to Muslim and Uyghur practice, lambs are not slaughtered too young and are always at least 6 months old.

Grapes and Raisins

I visited Turpan in the Spring, so the vines were just leafing out and climbing their frames from their long winter rest. The winter climate is so severe in Xinjiang that the vines are dug under and covered each autumn to protect them from the temperatures which can fall as low as -20°C and are accompanied by biting winds. The hot dry climate in the summer provides a taste advantage when towards the end of the growing season irrigation is decreased and the sugars are allowed to set in the grapes.

Some grapes are harvested as early as July and some last on the vine until autumn. Grape growers store some of their grapes in cellars or storehouses so as to have fresh fruit during the winter and spring months, but even more grapes are dried for raisins. Grapes are dried in mud-brick buildings – checkered with holes to allow circulation of air – called qunje in Uyghur. The grapes are left in the qunje for thirty or forty days, by which time they have turned into full, succulent sweet raisins which still retain the color and luster of fresh grapes. Sometimes, the grapes are allowed to dry for a few days in the sun before being hung in the qunje to make a sweeter variety of raisin.

I sampled seven different types of raisins while I was in Turpan. In general, the lighter colored raisins – white and green were more sweet than the darker reddish varieties. Most were seedless, but a few had noticeable seeds. They were all sweet and delicious, but the seeded varieties seemed to have the most complex flavors – being tart and sweet at the same time.

Wine

After sampling several wines from Xinjiang and Gansu, I found all of the wines were clean and fresh. They are light to medium-bodied, and have a short to medium length finish. On the downside, they are thin on the palate with very little concentration or intensity, and next to no complexity. They are good, but at this point, by western standards, they are not great. However, they please the domestic market and have done so for the better part of two millennia so far. Whether they will ever become wines that sell on the international market remains to be seen. The Chinese are interested in developing wine tourism and an internationally marketable wine industry, and are taking steps to do so. When I was in Turpan, they had just had a consortium of Napa Valley winemakers visiting for consultation.