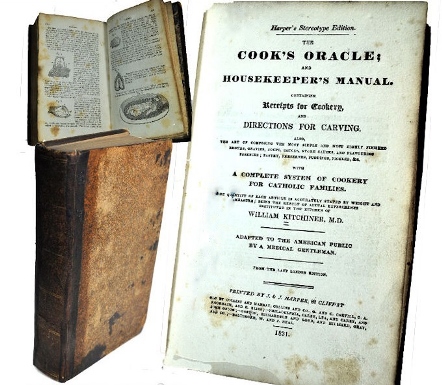

Today’s exploration of Indian Curry through Foreign Eyes takes us back to early 19th Century England to The Cook’s Oracle by Dr. Kitchiner, which was first published in London by Samuel Bagster in 1817. The original title of the book is Apicius Redivivus, or Apicius Reborn, so it is clear that the publisher thought that this book was a masterpiece of gourmet dining. Either that, or he simply wanted to cash in on the image of Apicius’s legendary dining habits in the sales of Dr. Kitchiner’s book.

The Kitchiner recipe for curry powder is an important one, and is cited as the basis of many recipes since then, including Mrs. Beeton’s and the curry powder used when the British introduced “Indian” curry to the Japanese in the late 19th Century.

In working with the Kitchiner recipes (No. 455 from both the 1817 and 1830 editions), I also think I have figured out why so many early curries and so many modern commercial curry powders have much more turmeric than any modern or historical Indian curry out there. The answer is simple: The confusion of grated, fresh turmeric root with dried and ground turmeric powder.

I have never seen an authentic Indian curry with more than a fraction of turmeric relative to the amounts of coriander and cumin. For example, if the recipe calls for 2-3 teaspoons of ground cumin and/or coriander, it will usually only call for about ¼-to- ½ -teaspoon of turmeric. Most Indian recipes use turmeric judiciously, almost in the way a bit of saffron is used to take the sharp edges off of the flavor of the other spices. On the other hand, try to find a mainstream, commercial curry powder that isn’t bright yellow or orange from the amount to turmeric in the mix. I have long wondered about this, and now think that adherence to “traditional” historical recipes may be the reason for this.

To try to prove this hypothesis, I cooked the Kitchiner curries with three ounces of fresh, grated turmeric root and found them to taste much more like and Indian curry than curries cooked with ground turmeric. This is not simply the difference between fresh and dried spice – a difference we all are aware of – but also of the relative proportion of the wet, grated root to the baked and dried powder in the recipe as a whole. An ounce of fresh root is much less turmeric than an ounce of ground turmeric, and the resulting flavor of the curry is radically different. It’s fascinating to me how a likely mistake in the 18th and 19th Centuries can still resonate today. Try it sometime with a favorite historical recipe and see if you agree about the turmeric issue. On to the recipes.

The 1817 Recipe for “Cheap Curry Powder” calls for four ounces of coriander seed, three ounces of turmeric, one ounce each of black pepper, ginger, and lesser cardamoms, and one-quarter ounce of cinnamon and cayenne. This recipe becomes a little gentler as time goes on, with later editions calling for three ounces of coriander seed and turmeric, one ounce of black pepper, mustard (an addition) and ginger, and half an ounce of lesser cardamoms, and a quarter ounce of cumin seed. Later American editions call for the addition of a half-ounce of allspice as well. Dr. Kitchiner observes in the later editions that the omission of the cayenne pepper from the recipe is to allow for cooks to add more curry powder according to taste without making the dish too hot. Written in modern form the recipes looks like this:

Dr. Kitchiner’s Curry Powder No. 455 (1817)

Ingredients

8 tablespoons coriander seed

6 tablespoons turmeric

2 tablespoons black peppercorns

2 tablespoons ginger

2 tablespoons green cardamom seeds

1.5 teaspoons ground cinnamon

1.5 teaspoons cayenne pepper

_____

Dr. Kitchiner’s Curry Powder No. 455 (1830)

Ingredients

6 tablespoons coriander seed

6 tablespoons turmeric

2 tablespoons black peppercorns

2 tablespoons mustard (an addition)

2 tablespoons ginger

1 tablespoon green cardamom

1 tablespoon allspice

1.5 teaspoons cumin seed.

Directions

The direction is to place all ingredients in a cool oven overnight, then to grind in a granite mortar and pass through a silk sieve. The sieving makes this a fine powder as opposed to a coarser, rustic grind.

Another reason for working with recipe No. 455 is that there is no specific recipe for a curry in the 1817 version of Dr. Kitchiner. Rather he suggests making curry sauces by adding curry powder a bit at a time to gravy or butter until a sauce pleasing to taste unfolds. There are recipes for deviled eggs, a bare-bones mulligitawny and a couple of curry-flavored forcemeats as well as a calf’s-head broth, but no meat stewed in liquid as the British had come to interpret as curry. I had to turn to a later edition if I wanted the Kitchiner curry recipe, and used the recipe from the 1830 edition instead.

Here is the original recipe for curries in the 1830 edition of Dr. Kitchiner’s The Cooks Oracle:

Curries (No. 497)

Cut fowls or rabbits into joints, and wash them clean: put two ounces of butter into a stew-pan; when it is melted, put in the meat, and two middling-sized onions sliced, let them be over a smart fire till they are of a light brown, then put in half a pint of broth; let it simmer twenty minutes.

Put in a basin one or two table-spoonfuls of curry powder (No. 455), a tea-spoonful of flour, and a tea-spoonful of salt; mix it smooth with a little cold water, put it into the stew-pan, and shake it well about till it boils: let it simmer twenty minutes longer; then take out the meat, and rub the sauce through a tamis or sieve: add to it two table spoonfuls of cream or milk; give it a boil up; then pour it into a dish, lay the meat over it: send up the rice in a separate dish.

Written in a more modern form, the ingredients looks like this:

Dr. Kitchiner’s Curries (1830)

Ingredients

1 – 1.5 pounds boneless fowl or rabbit (more if using meat on the bone)

4 tablespoons unsalted butter

2 large yellow onions

1 cup chicken broth

2 tablespoons curry powder (No. 455)

1 teaspoon flour

1 teaspoon salt

water to make a thin paste of the above three ingredients

2 tablespoons of whole milk or cream

The method from the original recipe is fairly straightforward. I made a couple of changes, searing the meat and removing it from the pan before adding the onions to the remaining butter, I added a bit more curry powder than called for, didn’t really boil the curry after adding the dairy, and I didn’t sieve the sauce before serving.

Note that the “cowboy roux” or “white wash” used at the end is a mix of flour, water, curry powder and salt and is used to thicken the sauce before finishing it with a bit of whole milk or cream. Because the Kitchiner recipe is so influential in the development of other western recipes for curry, I suspect that this recipe is probably where East Asian curries adopted their “curry roux” from, because the British introduced their version of Indian curry to Japan in the late 19th Century. More about that in future posts.

So what do these curries taste like? To me, the Kitchiner curry using the 1830 curry powder tastes like a more robust version of the Hannah Glasse curry (1774) which used only turmeric, ginger and black pepper (with a little lemon juice) for spice. It’s good, but it’s very turmeric heavy and almost completely lacks any cumin flavor, which is understandable given the proportionally miniscule amount in the curry powder. It also has none of the nutmeg and mace that Mary Randolph wrote about in 1824. The 1817 version of the powder that has the extra 2 tablespoons of coriander seeds, the two tablespoons of green cardamom seeds, and 1.5 teaspoons each of cinnamon and cayenne has a nice kick to it that is lacking in the 1830 curry powder. The overwhelming flavor of turmeric is less overwhelming in the earlier version. It’s a pity that this earlier version of the curry powder didn’t endure.

Both recipes also taste more authentically “Indian” with the use of three ounces fresh turmeric instead of three ounces of dried powder. (Words and historical recipe development by Laura Kelley; Photo of The Cook’s Oracle from Gunsight Antiques; Photo of Turmeric, Two Forms from Wikipedia and merged by Laura Kelley; Photo of Dr. Kitchiner’s Chicken Curry by Joseph Gough@Dreamstime.com)