Move over Hannah Glasse. Your published recipe for butter chicken that is widely hailed as the first English recipe for curry, has an English contender. In a 1675 anonymous manuscript full of recipes and potions in the Wellcome Library in London (Wellcome Manuscript 4050) is an English recipe for a vindaloo-flavored roast. In the recipe, cloves, mace, and lots of black pepper form the spice base. This is then mingled with some minced sweet herbs and mixed with vinegar for a marinade and baste for the roast. Not a vindaloo stew or braise like we are accustomed to today, but a recipe for vindaloo-flavored roast hen, mutton, or lamb. A proto-vindaloo, if you will.

Of course, there is an earlier published recipe for a curry than Glasse. The recipe entitled, A Curry for any Fish can be found in the 1680 edition of Arte de Cozhina by Domingos Rodrigues. But because it is in Portuguese, it is often passed over by people writing about the spread of curry into Europe and the Americas. Like the 1675 recipe, Rodrigues’ recipe is not in the form of a stew or braise, but rather it is a thick sauce to be ladled on top of a poached fish. The recipe specifies that it is also good for meat, but not for seafood.

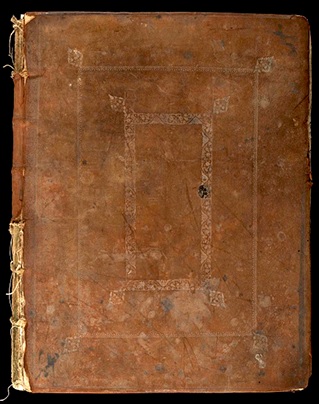

Older than either Glasse or Rodrigues, however, is the recipe for vindaloo-roast in the 1675 Wellcome manuscript. Tucked unassumingly onto the bottom of a page with recipes for hare, venison, and mutton (along with some recipes for pancakes and jelly) is a recipe entitled: “To Dress a Hen, Mutton or Lamb the Indian Way.”

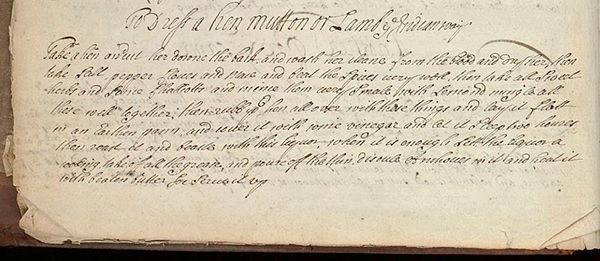

The recipe reads:

To Dress a Hen, Mutton or Lamb ye Indian Way

Take a hen and cut her down the back and wash her from the blood and dry her, then take salt, pepper, cloves and mace and beat the spices very well, then take also sweet herbs and some shallots and mince them very small with lemon and mingle all these well together; then rub up the hen all over with these things and lay it flat in an earthen pan and cover it with some vinegar and let it steep two hours; then roast it and baste with this liquor—when it is enough, set the liquor a cooking, take off the grease, and pour off the hen; dissolve anchovies in it and heat it with beaten butter. So serve it up.

A more modern presentation of the recipe prepared with a chicken would read:

Vindaloo Roast Chicken, 1675

Ingredients

1 small 4-4.5 pound chicken

2 teaspoons salt (or to taste)

1 tablespoon peppercorns

8 whole cloves

1½ teaspoons mace

6 shallots, peeled and minced

Leaves from two sprigs of rosemary

¼ cup minced parsley

¼ cup minced cilantro

2 teaspoons fennel seeds, ground

Zest from two lemons, minced

2 cups of white wine vinegar

2-3 tablespoons unsalted butter

1 handful dried anchovies

½ teaspoon cornstarch to thicken gravy (optional)

Directions

Wash and dry the chicken and split it down the back. Flatten the bird by pressing it down with a heavy saucepan. Grind the cloves and the peppercorns and mix them with the salt and 1 teaspoon of the mace. Add the minced shallots, the rosemary, parsley and cilantro. Grind the fennel seeds and add them to the herb and spice mixture. Add the lemon zest and mix well.

Coat the bird on both sides with the spice mixture and then lay it as flat as possible, skin side down, in a ceramic or enamel baking dish. Add the vinegar around the edge of the bird, and spoon some over the bird without washing the herbs and spices away. Cover and let marinate for at least 2 hours. Preheat the oven to 375 degrees F. while the bird is marinating.

When ready to cook, lift the bird out of the pan and place it on a plate. Then pour the marinade into a bowl. This will be used to baste the chicken as it cooks. Place a rack inside the ceramic or enamel pan and place the bird on it skin side up. Place into preheated oven.

After about 20 minutes, place the pats of butter on the chicken and place back in the oven. Lower heat to 350 degrees F. Every 10-15 minutes throughout the baking time, baste the chicken with the marinade. After about ½ hour, flip the bird over so it is skin side down. Cook this way for about 15-20 minutes and flip it skin side up. Total cooking time for a 4-4.5 pound bird should be about 1.25 – 1.5 hours. While you bake, mince the anchovies. I left the head and spine intact, and strained them from the sauce later.

When the bird is done, remove it from the pan and set aside in a warm spot. Pour the mixture of marinade and cooking juices into a small saucepan, and if you desire, skim the fat from the top. Then add the anchovies. Heat, but do not boil, and cook for 5-10 minutes, stirring constantly, to mingle the flavors. Then strain the solids from the gravy. I used a fine sieve lined with cheesecloth.

Return the strained sauce to a cleaned saucepan and reheat for another 5-10 minutes, watching that it doesn’t boil. Add the remaining mace and mix well. If the gravy doesn’t thicken enough as it reduces, take about ¼ cup of the sauce and put it in a teacup or small bowl. Add some cornstarch to the cup and whisk or mix well with a fork to break up the cornstarch. Whisk the sauce in the saucepan and drizzle the mixture of cornstarch and gravy until the gravy thickens up to your desired consistency.

Carve and plate the bird and spoon a small amount over the chicken. Serve the remaining gravy on the table for diners to add at will. I did not reheat the bird, given the tendency for people in the past to eat dishes warm or cooled, but not hot.

_____

The bird was really delicious. The sauce made with the mace and vinegar was fantastic! Although I was a bit skeptical about this recipe being a proto-vindaloo based on the ingredients, it very much tastes like I would expect and early European version to taste. If that seems a bit convoluted, just think how the butter chicken recipes of de Peyster or Glasse in the 18th Century compare with modern versions of the recipe. Minus the tomato sauce in many modern versions, the taste is different, but it is clearly an attempt to recreate Indian flavors. Likewise, this recipe from Wellcome manuscript 4050, is definitely an attempt to recreate the flavors of an Indian vindaloo.

The major difference between my version and the original recipe was extra mace added in the sauce to balance out the overwhelming taste of vinegar. In fact, I think that there was such a tendency for the vinegar to overpower the herbs and spices used on the bird, that I would use much less of it in subsequent preparations. One way to do this would be to use about 1 cup for the marinade. Another way would be to skip the vinegar in the marinade, and just baste the bird with ¼ cup of vinegar in addition to the butter and cooking juices. Minus the vinegar, I would also let the herbs and spices sit on the bird for a longer amount of time, perhaps even overnight.

Another change I made was to put the butter on the chicken as it was roasting rather than add it to the sauce as it is being reduced after cooking.

As with many modern recipes from the Silk Road, this recipe gives a lot of freedom to the cook to alter amounts of ingredients or even whole ingredients. In this early recipe there is the direction to, “then take also sweet herbs.” I chose parsley, rosemary, and cilantro with a bit of added ground fennel seeds. Different choices would lead to different flavor, especially with less vinegar in the mix.

_____

For me, cooking this recipe and enjoying the dish with my husband on our 20th wedding anniversary was a wonderful experience. It was like time traveling with a delicious twist. Eating a dish that was cooked when Charles II was restored to the throne of England was fascinating.

Think about 1675 for a moment. Subcontinental flavors were creeping into European cuisine, and interest in eastern cultures that wasn’t purely economic was on the rise. The importance of science in society was taking a more modern shape as the cornerstone for the Greenwich Observatory was laid, Leibnitz was demonstrating integral calculus, and van Leeuwenhoek was opening doors to the microcosm. All in all, the globalized world that was being created by the the massive trading corporations was smaller than that fueled by Silk Road trade.

From a European perspective, however, the world was also more diverse and complex place than ever before. New species were being discovered on a nearly daily basis, and early travelogues and anthropologies added faces and customs to the people from far-off lands. Sea monsters began to disappear from maps as man gained greater mastery over the seas, and science replaced mythology and folklore with anatomic description. Europe was on the doorstep of The Enlightenment, and this is what at least one English family might have been eating.

(Words by Laura Kelley. Photographs of Wellcome manuscript 4050 from the Wellcome Trust. Photograph of Vindaloo Roast Chicken by Laura Kelley.)

1 thought on “A 1675 Vindaloo Roast Chicken”